In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 190.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved long poems. My first introduction to poetry came from epics I read before I could possibly understand them, books my father owned and half-read: The Divine Comedy, The Odyssey, The Iliad, The Aeneid, El Cid, Orlando Furioso. When I started writing poetry myself, I was drawn in by the modernist attempts at epic: the Cantos of Ezra Pound; William Carlos Williams’s Paterson, published in five volumes between 1946 and 1958 by New Directions; and H.D.’s Helen in Egypt (Grove Press, 1961). Then, as an undergraduate wandering the stacks of the Glenn G. Bartle Library at Binghamton University, I discovered A. R. Ammons’s Garbage (Norton, 1993) and Tape for the Turn of the Year (Norton, 1965). Around the same time, my poetry professor, Liz Rosenberg, assigned The Book of Nightmares (Houghton Mifflin, 1971) by Galway Kinnell. Kinnell and Ammons hooked me with their discursive, gamboling, digressive, ambitious, sprawling, yet unmistakably cohesive poems. I started writing poems too long to bring into workshops and too obscure to make sense to anybody but me. Later on, I would find Ruth Stone’s Who Is the Widow’s Muse (Yellow Moon Press, 1991) and William Heyen’s To William Merwin (Mammoth Books, 2007), two book-length poems that never cease to amaze me with their propulsive brilliance. At some point along the way, I also read Rachel Zucker’s “An Anatomy of the Long Poem,” which she recently included in the appendix of her book The Poetics of Wrongness (Wave Books, 2023). My thoughts on the long poem inevitably trace back to Zucker’s many insights; Zucker’s essay confirmed for me that I should continue trying to write a book-length poem. Reading The Poetics of Wrongness after the University of Wisconsin Press published my book-length poem, Midwhistle (2023), affirmed the conclusions I’d made through my writing process.

Before writing Midwhistle and reading The Poetics of Wrongness, I had assumed that writing a poem longer than a page-and-a-half Word document was beyond my capabilities. I had tried and failed for twenty years to write longer poems, while keeping in mind that writing a good poem of any length is an accomplishment, a thing that isn’t merely lucked into being. Book-length poems—or poetry collections that read like book-length poems—kept calling to me from my reading life: Claudia Rankine’s Citizen (Graywolf Press, 2014), Derek Walcott’s Omeros (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990), Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red (Vintage, 1998), Edward Hirsch’s Gabriel (Knopf, 2014). Add to that list a growing number of book-length projects or poetic sequences: Crow by Ted Hughes (Faber and Faber, 1970), Barbie Chang (Copper Canyon Press, 2017) by Victoria Chang, Olio (Wave Books, 2016) by Tyehimba Jess, Sand Opera (Alice James Books, 2015) by Philip Metres, the many books of H. L. Hix. The list of long poems I admire could go on and on, including those by Ronald Johnson, James Schuyler, John Ashbery, Melvin B. Tolson, and, of course, Walt Whitman and William Blake. These works are so disparate in their thematic concerns and technical approaches as to be almost unrecognizable as a category or type. What I love about long poems is what I love about poetry in general: Long poems are not monolithic; they thrive on acute heterogeneity and multivalent strangeness.

If I had to constellate the many long poems (and long-poem-adjacent projects) I love, I’d have to rely on Rachel Zucker’s brilliant observations. Zucker argues that a long poem (1) is extreme, (2) grapples with narrative, (3) takes time to read, (4) is confessional, (5) creates intimacy, (6) is “about” something AND is about nothing but itself, (7) resists “aboutness,” is instead muralistic or kaleidoscopic, (8) discovers itself, (9) allows the poet to change her mind, (10) changes the mind of the reader and the writer, (11) is ambitious, (12) humbles the poet, (13) highlights process, (14) is imperfect. I found all these observations to be true when writing Midwhistle.

I started writing Midwhistle without knowing I was beginning a book-length poem. I’d just watched a YouTube video of William Heyen reading his poetry. I had been corresponding with Heyen, who is in his eighties, and I found his work and life to be resonant with my own, reconciling as it did a kind of suburban conformity with a radical, quixotic ambition to make great poetry. My wife was pregnant with our second child. We were living through the pandemic and emerging from the chaos of the Trump presidency. I began writing a poem, a single column of seven syllable lines, addressed to both my octogenarian poet-friend and to my unborn child. Before I knew it, I had written ten pages in one sitting. A few days later, I went back to what I wrote and saw it was pretty good (as Larry David would say). I printed off a copy and sent it to Heyen. He wrote back telling me I should develop it into a book-length poem and suggesting I should break the stichic column into cinquains, or five-line stanzas. From there, I developed a stanzaic pattern that zigzags like a double helix. The poem unspooled like an umbilical c(h)ord from there. I felt like I could put anything and everything into this poem, even my own imperfections—all my wrongness and all my love. The poem was my way of saying everything-beyond-saying about poetry and the world—for the future adult my unborn son would one day be, and to the poet I revere.

I wrote the poem at intervals over a two-month period. I imagine I worked in the way an undisciplined novelist might work, incrementally and at odd intervals. Once I had around fifty pages done, I set it aside for a month. Then I reread it and began making initial revisions. I sent it to William Heyen. He sent back encouragement. I revised for several more months and then sent it out to University of Wisconsin Press. Fortunately for me, Ron Wallace and Sean Bishop saw the strength in what I had written and decided to publish it. I worked on revision intensively for the next couple of months and then proofread draft after draft along with the exceptionally diligent copy editors at the press. I spent more time revising the twenty-four sections of Midwhistle than I have with any poem in my life.

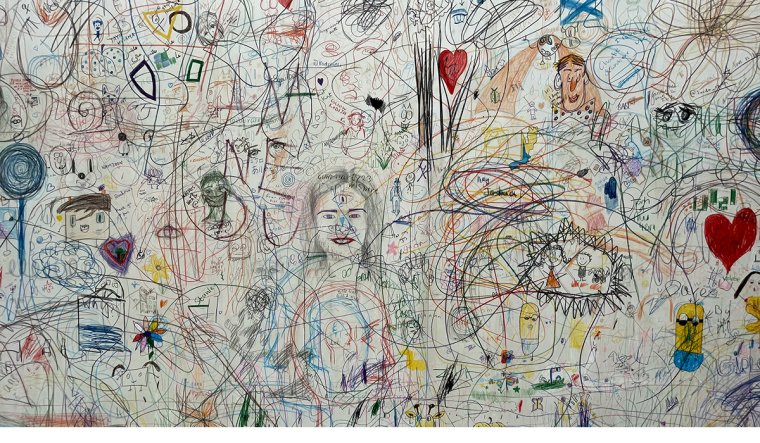

Dwelling in the long poem allowed me to understand better the tropes and thematic concerns that populate my body of work. My obsessions and my quirks fanned out before my eyes. I came to see all my poetry as an intimate conversation with my wife and kids and with the poets and poetry I love. I came to embrace my flaws, my extremities, my ridiculousness. Poetry became more intimate for me than ever, more sacred, and at the same time closer to the rhythms of the ordinary and the unvarnished. I felt that I’d accomplished something as epic as the crayoned fire in one of my five-year-old daughter’s 8.5 x 11–inch landscapes. I felt like a stick figure king arrayed in ROYGBIV and counting to one hundred. From that vantage point, even the briefest lyric fragment expands like a pocket universe, and the distance between short and long poem collapses entirely. For those daunted by the prospect of writing a book-length poem, I would offer the advice that I would give my younger self if I could: Be patient. Keep reading long poems that delight and undo you. Be prepared to fail many times. But gather the bouquet of those failures close to your heart, and let their aromas inspire momentum and ambition in you. Lastly, keep writing more and differently—for the love of writing, the way my daughter sketches her vibrant Crayola kingdoms and queendoms, letting the irrepressible, ancient, innate music of the self take shape on paper.

Dante Di Stefano is the author of four poetry collections, including the book-length poem Midwhistle (University of Wisconsin Press, 2023), Love Is a Stone Endlessly in Flight (Brighthorse Books, 2016), Ill Angels (Etruscan Press, 2019), and Lullaby With Incendiary Device, which was published in an anthology titled Generations (Etruscan Press, 2022) that also includes poetry collections by William Heyen and H. L. Hix. Di Stefano’s poetry, essays, and reviews have appeared in The Best American Poetry 2018, Prairie Schooner, the Sewanee Review, the Writer’s Chronicle, and elsewhere. With María Isabel Alvarez he coedited the anthology Misrepresented People: Poetic Responses to Trump’s America (NYQ Books, 2018). He holds a PhD in English from Binghamton University and teaches high school English in Endicott, New York. He lives in Endwell, New York, with his wife, Christina, their daughter, Luciana, their son, Dante Jr., and their goldendoodle, Sunny.

Art: John Cameron