In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 209.

The proprioceptive nervous system is fascinating. Every millimeter of our bodies is covered with a rhizomic net of tiny interconnected nerves—the proprioceptors—right below the skin and embedded in all of our muscles, which handles balance and motor control. Our proprioceptors are like our antennae, constantly picking up subliminal data from within our bodies and from the outside world. They’re like our “spider-senses.”

What would happen if we could write directly from our spider-senses?

I once had a short foray into stagecraft, and from that experience, I learned that there’s a difference between acting and what cinema and theater folks call “indicating.” To indicate is to smile, for instance, when you’re trying to show happiness. But an actor showing happiness doesn’t smile; a good actor showing happiness to an audience starts by recalling memories of happy times in their lives, and then conjuring actual feelings of happiness. Then, the actor’s face and body glow with that feeling, and that feeling is transmitted to the audience.

I think writers can benefit from the same practice—to stop “indicating” on the page and start expressing real feelings. For example, if you’re writing about joy, perhaps you recall a collection of moments when you were happy, or you remember a piece of joyful music, and that memory makes your body respond, and perhaps you feel your chin lift slightly, and your breath shortens, and a catch rises up and stops in your throat, and then you can find language from that place of feeling, to render joy onto the page. Actors call extreme instances of this technique “method acting,” and I’m a big advocate of the concept of going into character and remaining in character while writing. Why not call it “method writing”? (Well, one reason why not has been illustrated by the great screenwriter Aaron Sorkin, who once broke his own nose while acting out the emotions and situations he was method writing about.)

My undergraduate creative writing students have learned to expect method writing exercises almost every day in my classes. We’ll all breathe together for a short time, becoming aware of our individual embodiedness, and we’ll meditate on a particular emotion—happiness, joy, anger, pain, lovesickness, understanding, confusion. Then we’ll endeavor to write images that reflect that emotion. The imagery my students produce always seems more vivid and considered if we first take a few moments to meditate upon the bodily sensations that might drive the image. Here are a few examples of method-written images students have composed for various emotions:

Desire:

A hand that never stops reaching

You take out my heart, grind it up, and inject it back into me bit by bit

Confusion:

A white Republican with a rainbow pride tattoo

Buzzing rainbow static brain

Heart galloping in place

Brain fibers twist and strain

Understanding:

A gray cat who comes when you call her name

The flickering basement bulb finally gets changed

Both of us cry at the end of a fight

Whether or not these images convey the emotions that inspired them, I find them all to be more or less vivid, visceral, weird, and wonderful. And they’re much stronger than the images my students write when they don’t tune into their feelings and go into their bodied imaginations to find them.

To state it plainly, if you’re going to “method write” from your feelings, then you need to be in touch with your body and the physical sensations that give rise to those feelings.

If you want to try the exercise I do with my students, first, pick an emotion or situation. Let’s say, “anxiety.”

Now, begin by simply breathing in and out.

Each time you breathe, make sure the breaths are very deep and considered.

See how the increased oxygen makes your head feel different.

Press your hands lightly together. Feel the texture of your palms.

Think about your posture. Adjust your head and back.

Make sure you’re breathing from your belly, not from your upper chest and shoulders.

Think about the soles of your feet as they touch the ground.

Think about your facial expression. Try to relax your face, perhaps even smile a little, even if you don’t mean it.

Let the tension release from your muscles. Keep your hands pressed together.

Now try to experience the sensations of all of your proprioceptors. What is the back of your neck telling you? The area behind your left knee? The very top of your head? One by one, try tuning in to the unconsidered parts of your body.

Now shift to considering your chosen emotion: “Anxiety.” Where does that emotion seem to begin? How does it spread? What shape does it take as it spreads? What’s happening to your heartbeat, your stomach, and your breath? How are your proprioceptors responding to the feeling of anxiety? Does the feeling seem to attach to an object in the world? It’s important to remember that you are having this emotion; don’t let the emotion have you, as it were. You are in control. (Not only has this exercise helped me write better, but it has also helped me to better master my feelings, instead of letting my feelings become the master of me. Perhaps an exercise such as this one can help you to only feel anxiety when you invite it, for writing purposes!)

Here are some images that I came up with for “anxiety.” I keep these images inside a notebook on a page marked “anxiety images,” for use whenever I’m in a writing session and I have a character who has a moment of anxiety, or a poem needs to shift through an anxious moment.

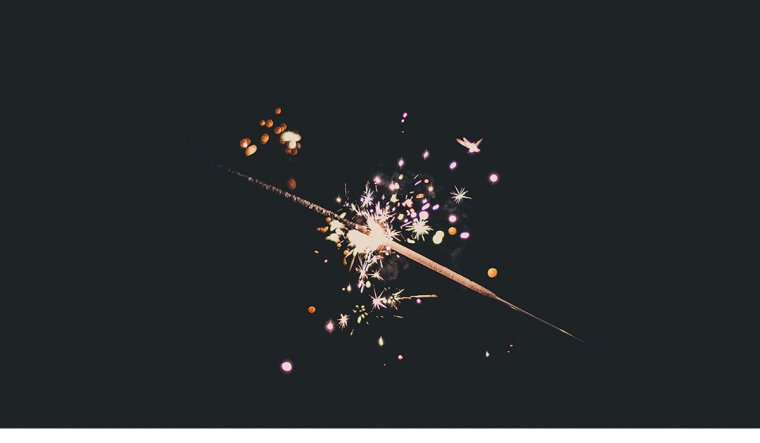

He clenched his hands together until they felt like a single hand. His teeth inside his closed mouth were like a bag of blunt nails. He was aware of the nerves inside his hairs. His spine huddled up to his lungs, and his whole face converged at a single point, lips at the tip. His ears were an inch apart, with a 4th of July sparkler fizzing between them. His skin had become a dense material. His forehead wadded like an unimportant piece of paper.

Method writing has helped me render emotions more vividly and viscerally. Perhaps these practices can do the same for you.

Geoff Bouvier’s new book, Us From Nothing (Black Lawrence Press, 2024), is a poetic history that spans from the Big Bang to the near future.

image credit: Jez Timms.