In our seventh annual look at the debut authors of some of the year’s most poignant, meditative, and experimental memoirs, essay collections, and memoirs in essays, David Martinez details the watershed events that led to the writing and eventual publication of his memoir about brotherly love and the wounds, both literal and metaphoric, that shape us; Wei Tchou compares the process of writing her innovative book on ferns, family lore, and selfhood to growing a propulsive tomato plant; Zara Chowdhary describes how finally reckoning with what was brewing inside her from a childhood spent surrounded by anti-Muslim violence allowed her to free herself; Lydia Paar explains how the privacy of the writing process and outside feedback led to an essay collection that untangles varied topics on the notion of transformation; and Neesha Powell-Ingabire reflects on the rebellious and healing act of writing a memoir in essays about the history of the Geechee Coast. This year’s The New Nonfiction feature includes five distinct debut journeys that reveal the thoughts, feelings, and actions behind each author’s writing and publication process, a process that started more or less the same for them all. As Tchou recalls, “Sometimes I think about how for a long time it was just me staring at a blank Google Doc, trying out some lines.” Below are excerpts from this year’s five debut books; read essays by the authors in the September/October 2024 issue.

Bones Worth Breaking (MCD, April) by David Martinez

Little Seed (A Strange Object, May) by Wei Tchou

The Lucky Ones (Crown, July) by Zara Chowdhary

The Exit Is the Entrance: Essays on Escape (University of Georgia Press, September) by Lydia Paar

Come by Here: A Memoir in Essays From Georgia’s Geechee Coast (Hub City Press, September) by Neesha Powell-Ingabire

Bones Worth Breaking

David Martinez

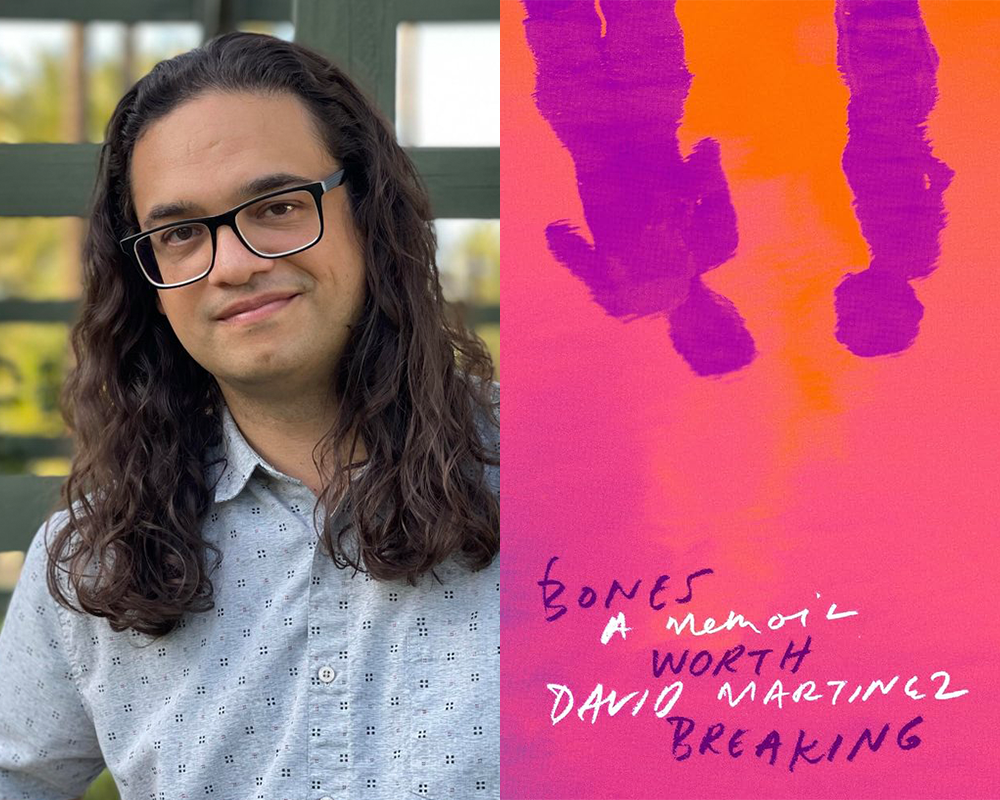

David Martinez, whose memoir, Bones Worth Breaking, was published by MCD in April. (Credit: Veronica Martinez)

Just a Flesh Wound

When I was maybe eleven, I walked into the bathroom and burned a piece of skin off the back of my hand on a curling iron. My aunt had left it plugged in for hours—it was hanging off the edge of the sink, waist high, and when I made contact the first layer of skin peeled away, leaving an indent the size and shape of a kidney bean. I thought it was okay at first—at least I don’t remember when it started to hurt, if it came with the shock of seeing a piece of my epidermis melted off, or if it was when I’d put it under cold water. I know it hurt when I applied the toothpaste—a neighbor had once told me it soothed burns. I had a hard time scrubbing the toothpaste out from the melted flesh. It burned mint-fresh for days. I didn’t let anyone see how bad it really was. My parents asked if I was okay. They scolded me on paying more attention and told me not to ever listen to irrational medical advice from stupid neighbors. They asked if I needed to see a doctor. Gripping my hand, careful not to put any weight onto the paste-filled concave, I said no. It was fine. I was fine. I didn’t show it to any adults until after it healed over. It seared red and infected around what had become a black scab mixed with fragments of white paste. It lasted days. Weeks. Longer. I hid it under a Band-Aid, and it eventually healed. Now I have a smooth, oblong scar between the bottom knuckle of my right index finger and thumb. But it’s okay. I’m okay.

![]()

There is nothing on my skin that shows where I was hit by a car, and then abandoned, while walking across a street in Rancho Mirage, California, when I was thirty-three. I have no scar. I wasn’t hurt. With no definitive proof of the incident, I’m not sure what to say. How can anything be important if it doesn’t leave a mark?

![]()

I don’t have a mark from when I broke my arm when I was ten. But I know it was my left arm because I was grateful that I could still write. It happened while I was visiting my grandparents for the summer in Genesee—on the sometimes green, sometimes brown and red, or white, rolling hills of the Palouse in northern Idaho and Washington. I broke my arm skating alone with loose, plastic Rollerblades at a school that sat on top of one of the infinite hills. By the time I hit the patch of grass that had been creeping up from the cracked sidewalk I was going so fast that my legs shook from the speed. Luckily, I managed to defy physics and push my body backward.

My arm didn’t go crooked or anything. It was just a hairline fracture. It wasn’t even immediately apparent it was broken. My great-grandmother—who was raised on a no-nonsense, Depression-era farm—assured me that I was fine. All I needed to do was roll my wrist around and move it as much as I could. “Like this,” she said, and twisted her hand in the air. I don’t remember how many days it took before we went to the hospital; it was sometime after I tackled my brother Mike, who had deep brown skin and straight black hair and an almost perpetual smile that showcased his crooked teeth. My best friend. We were in the neighbor’s slanted yard playing some game we’d made up. My bone was already broken, so falling on top of it with Mike just broke it a little more. The doctor said, “Hey, you want to see what a broken arm looks like?” before pulling up the X-ray. I can’t see it now, but I know I did see it then. Plus, there were witnesses. It’s always better to have witnesses. It doesn’t hurt anymore though. It’s okay.

![]()

I knew the car was coming before I stepped off the sidewalk. It was one of those moments when time slows and the body moves on its own and everything is silent except your thoughts. I knew the car was coming, but I kept walking, no longer in control. The car was low and blue and expensive, the driver oblivious and small—her head not completely visible over the steering wheel. By the time she made contact, I was in the middle of the street. My body reacted like it did in my skateboard days; I jumped without thinking. My body said up, and I went up, landing with both feet on the hood. Everything was so slow that I had time to look at my shoes and consider how the Converse-pattern soles would leave a distinct mark on her car. Already familiar with the rhythm of collisions, I felt velocity beneath me and imagined how much force I would have to transfer to fall onto the windshield if the woman’s reaction was too slow and she kept moving. But she stopped, and time resumed, and I fell backward. My right foot hit the asphalt. I crouched as I fell, my left arm behind me, and rolled. I felt the thud on my arm and thought, it’s okay if it breaks again. I’ll still be able to write.

Excerpted from Bones Worth Breaking: A Memoir by David Martinez. Published by MCD, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2024 by David Martinez. All rights reserved.